How an Atari Game Was Designed and Manufactured: From Idea to Cartridge

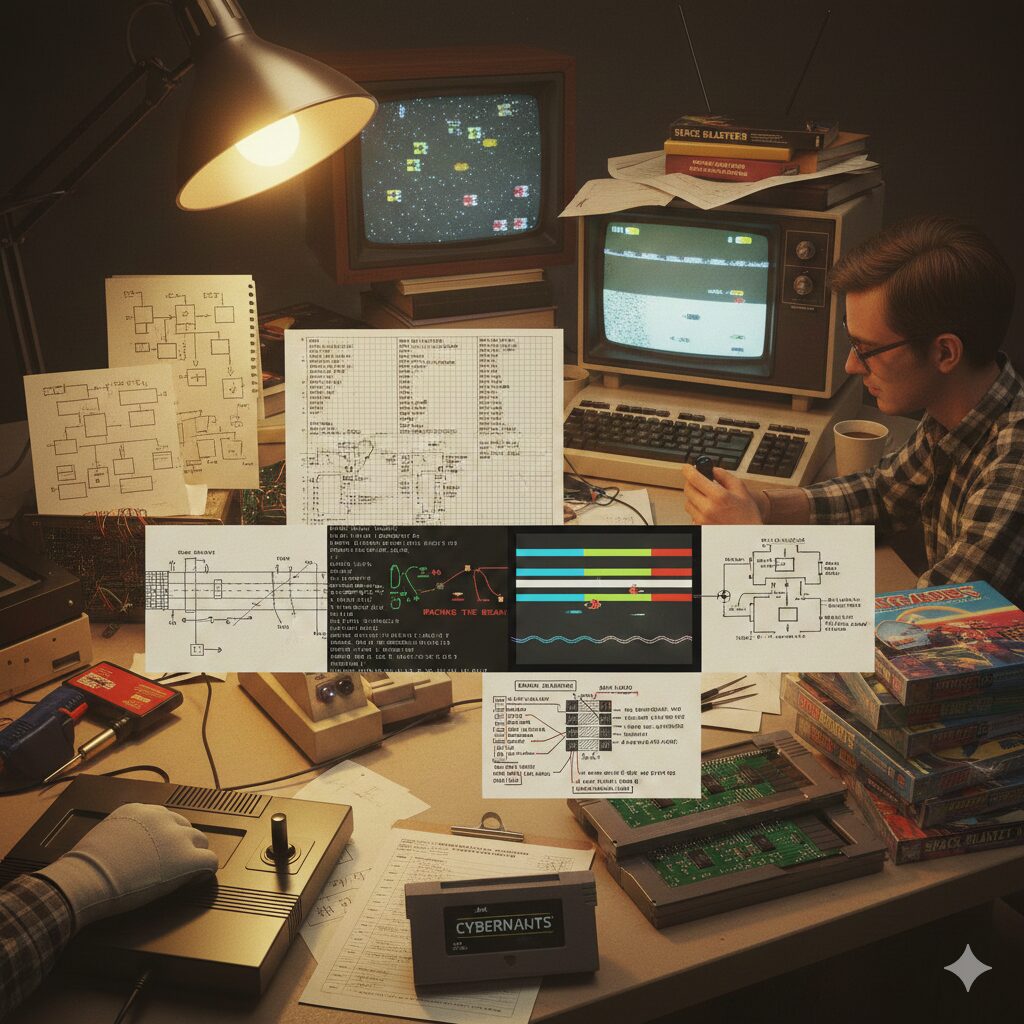

Creating a game for the Atari 2600 in the late 1970s and early 1980s was nothing like modern game development. There were no engines, no debuggers, no operating system, and no safety net. Developers were forced to think like hardware engineers, working directly with the machine at the lowest possible level.

This article walks through the complete process of creating an Atari game—from the first idea all the way to a finished cartridge sitting on a store shelf.

Step 1: Designing an Idea That the Hardware Could Actually Run

Before any creative ideas could take shape, developers had to ask a brutal question:

Because of these limits, early game concepts were intentionally simple:

- Single-screen gameplay

- Very few moving objects

- Minimal animations

- Little or no text

Games were designed around what the hardware could do, not what the designer imagined.

Step 2: Planning Everything on Paper

Before writing code, developers planned the entire game on paper. This included:

- Exact sprite positions for each scanline

- CPU cycle timing

- Memory allocation

- When logic could safely run during vertical blanking

This step resembled circuit design more than software development.

Step 3: Dividing the 128 Bytes of RAM

Memory management was critical. With only 128 bytes of RAM available, every variable had to be carefully planned.

$80 - Player X position

$81 - Player Y position

$82 - Enemy X position

$83 - Enemy Y position

$84 - Score

$85 - Timer

There were no abstractions—just raw memory addresses.

Step 4: Writing the Game in 6502 Assembly

All Atari games were written directly in 6502 assembly language. There were no high-level languages or engines.

Start:

LDA #0

STA GRP0 ; Clear player sprite

STA COLUBK ; Set background color

The code was divided into three main sections:

- VBlank logic – game calculations

- Kernel – real-time screen drawing

- Overscan – cleanup and preparation

The Kernel had to be cycle-perfect. A single missed clock cycle could break the display.

Step 5: Drawing the Screen in Real Time

The Atari had no framebuffer. Instead, the CPU had to feed the graphics chip while the television was actively drawing the image.

For each scanline, the CPU had to:

- Position sprites

- Set colors

- Trigger drawing at the exact right moment

Many visual effects were actually timing tricks rather than true graphics features.

Step 6: Testing on Real Hardware

Early developers did not have reliable emulators. Testing was done on actual Atari consoles connected to real televisions.

Common issues included:

- Screen flicker

- Color distortion

- Loss of synchronization

Some bugs appeared only on certain TV models.

Step 7: Aggressive Optimization

When the ROM was almost full, developers entered a phase of intense optimization:

- Removing redundant instructions

- Merging logic paths

- Using self-modifying code

- Reusing memory locations

Saving a single byte could mean adding a new feature.

Step 8: Overcoming ROM Size Limits

If a game grew beyond 4 KB, developers implemented bank switching.

Writing to a specific memory address would:

- Trigger hardware inside the cartridge

- Swap a different ROM bank into the CPU’s address space

Software directly controlled physical hardware behavior.

Step 9: Creating the Master ROM

Once the game was finished:

- The final binary was produced

- A master ROM image was created

- EPROM chips were programmed

Each chip contained the complete game.

Step 10: Manufacturing the Cartridge

The ROM chips were soldered onto small circuit boards. These boards were then placed inside plastic cartridge shells with edge connectors.

Each cartridge became a physical extension of the console.

Step 11: Quality Control

Every cartridge was tested to ensure:

- The game booted correctly

- No graphical glitches appeared

- The hardware connection was reliable

There were no patches or updates—what shipped was permanent.

Step 12: Packaging and Distribution

Finally, the cartridges were packaged with printed manuals and box art. The game was shipped to retailers and entered the market.

Conclusion

Developing an Atari game was not just software development—it was precision engineering. Every frame, every byte, and every clock cycle mattered.

The finished cartridge represented months of hardware-aware craftsmanship, forever frozen in silicon.

#Atari #Atari2600 #RetroGaming #GameDevelopment #GamingHistory #VideoGameHistory #RetroTech #VintageComputing #6502 #AssemblyLanguage #LowLevelProgramming #HardwareEngineering #ClassicGaming #GameDesign #TechHistory

Leave a Reply