How Atari Cartridge Games Really Worked

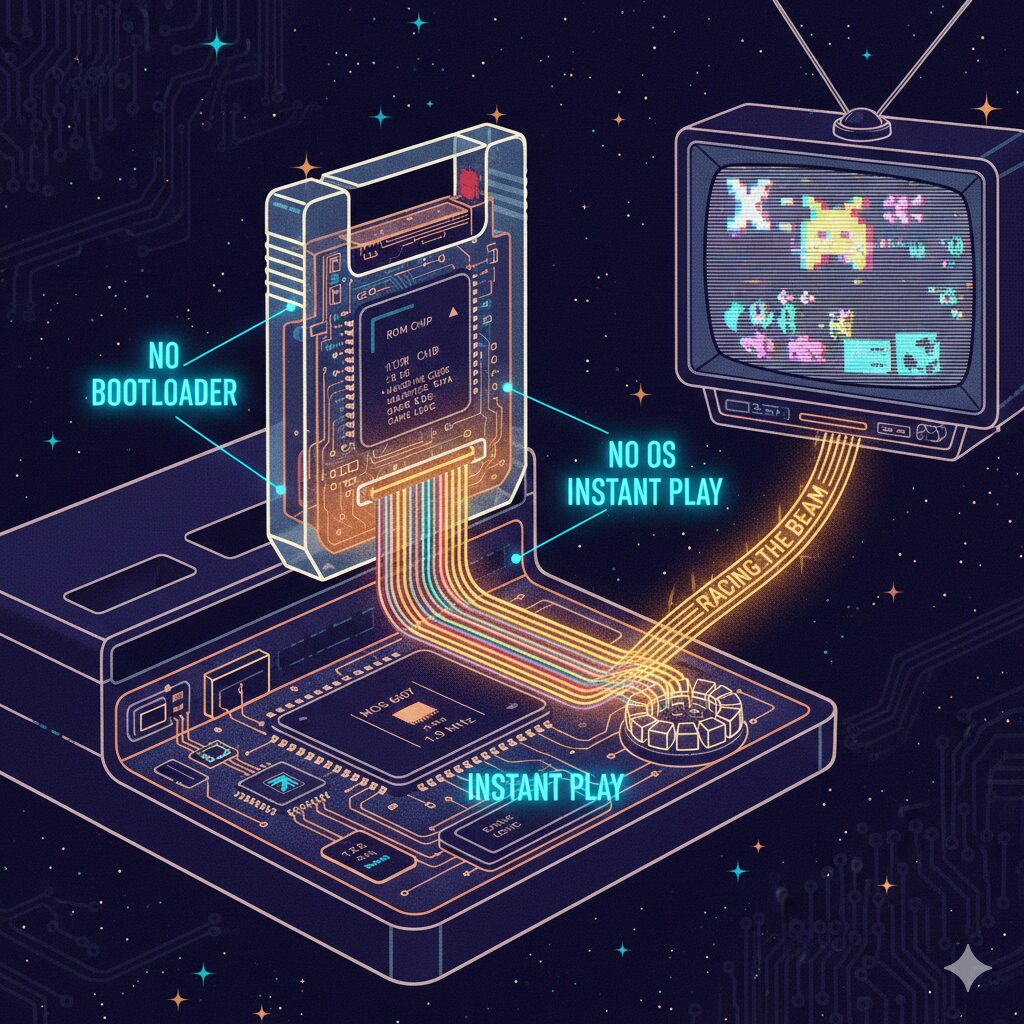

In the early days of home gaming, consoles like the Atari 2600 felt almost magical. You inserted a plastic cartridge, flipped a switch, and instantly a game came to life—no loading screens, no operating system, no installation. But behind this simplicity was an incredibly clever combination of hardware and low-level software design.

This article explains how Atari cartridge-based consoles worked, what was inside the cartridges, and how games ran at both the hardware and software levels.

The Big Picture: What Happened When You Inserted a Cartridge?

Unlike modern storage media, Atari cartridges were not passive data containers. They were active hardware components that plugged directly into the console’s internal bus.

When a cartridge was inserted:

- The CPU executed code directly from the cartridge’s ROM

- No operating system was involved

- No files were loaded into memory

- No bootloader or software layer existed

The cartridge effectively became part of the console itself.

What Was Inside an Atari Cartridge?

1. ROM (Read-Only Memory)

The core component of every cartridge was a ROM chip. Typical sizes were extremely small by modern standards:

- 2 KB

- 4 KB

- 8 KB (for more advanced games)

This ROM contained:

- Machine code (6502 assembly)

- Graphics data

- Sound data

- Game logic and rules

There were no game files or assets in the modern sense—only raw executable code.

2. Extra Hardware (In Some Cartridges)

More advanced cartridges included additional hardware such as:

- Bank-switching logic

- Small RAM chips

- Specialized support circuits

This allowed cartridges to overcome console limitations and expand the system’s capabilities.

What Was Inside the Atari Console?

The CPU

The Atari 2600 used the MOS 6507, a cost-reduced version of the famous 6502 processor.

- Clock speed: ~1.19 MHz

- No hardware interrupts

- Extremely limited address space

RAM

The console had only 128 bytes of RAM. Not kilobytes—bytes.

The TIA (Television Interface Adapter)

The TIA chip handled:

- Graphics output

- Sound generation

- Synchronization with the television signal

Crucially, the Atari had no framebuffer. The screen was not stored in memory. Everything was drawn in real time.

How Did Games Actually Run?

Power-On Execution

When the console was powered on:

- The CPU began executing instructions from a fixed memory address

- That address pointed directly into the cartridge ROM

- The game code started immediately

There was no boot sequence beyond this.

The Infinite Game Loop

An Atari game was essentially a single infinite loop:

while (true) {

Draw the next scanline

Update object positions

Check collisions

Generate sound

}

Real-Time Graphics: Racing the Beam

Television displays draw images line by line from top to bottom. The Atari CPU had to keep up with this process in real time.

This technique became known as “Racing the Beam.”

For every scanline, the CPU had to:

- Position sprites

- Set colors

- Trigger drawing at precise clock cycles

The result was an intense synchronization between software and hardware.

Sprites and Visual Tricks

The TIA supported only a few on-screen objects:

- Two player sprites

- Two missiles

- One ball

Games that appeared to show many enemies achieved this by:

- Reusing the same sprite multiple times per frame

- Changing positions mid-scanline

- Exploiting human visual persistence

Many “multiple enemies” were actually the same object drawn repeatedly at different times.

Bank Switching: Beating the Memory Limit

The CPU could only address a small section of ROM at once. To use more memory, cartridges implemented bank switching.

Writing to a special memory address would:

- Trigger hardware logic inside the cartridge

- Swap a different ROM bank into the CPU’s address space

This meant software could dynamically control physical hardware.

Why It Felt Like Magic

The Atari experience felt magical because:

- The cartridge became part of the machine

- Games ran instantly

- There was no abstraction layer

- Every CPU cycle mattered

Developers were not just writing games—they were choreographing hardware in real time.

Conclusion

Atari cartridge games were a masterpiece of constraint-driven engineering. With tiny amounts of memory and limited hardware, developers created experiences that defined a generation.

Each cartridge was not just a game, but a physical extension of the console itself—proof that creativity thrives under limitations.

#Atari #Atari2600 #RetroGaming #GamingHistory #VideoGameHistory #ClassicGaming #GameConsoles #RetroTech #ComputerHistory #TechHistory #OldSchoolGaming #HardwareEngineering #LowLevelProgramming #AssemblyLanguage #6502 #VintageComputing #GameDevelopment #SoftwareEngineering #TechExplained #Nostalgia

Leave a Reply